In June this year, His Honour Judge McGill SC of the District Court, Brisbane delivered a decision concerning costs of a Family Provision Application involving a small deceased estate (Baker v Baker (No.2) [2019] QDC 140). The Applicants in that case, the surviving spouse and adult son, achieved an order in their favour on the trial. However the issue left to be resolved were what costs orders should be made from the estate in favour of the Applicants on the one hand and the executor of the estate, upholding the Will of the deceased on the other.

Judge McGill rejected an argument advanced to him that the executor of the estate was entitled to be paid their costs on an indemnity basis. In doing so, His Honour said “the position, in my view, is that, particularly in smaller estates, there is a particular obligation on the parties to litigate efficiently and to minimise the costs of that litigation, and the function of Rule 700A (of the Uniform Civil Procedure Rules 1999) is to permit the Courts to penalise parties that litigate extravagantly or inefficiently. The smaller the estate, the more important it is that the costs of the proceeding be minimised. Otherwise, a situation can easily arise where the estate will be consumed simply by the costs of litigation.”

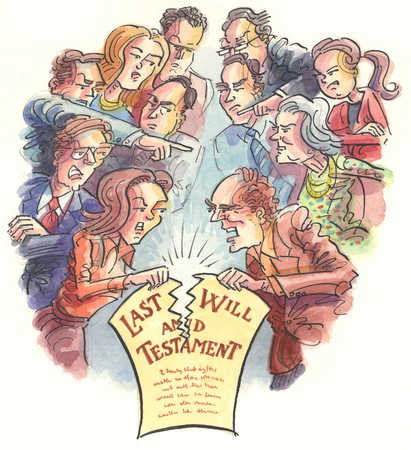

His Honour added “Given that Family Provision Applications frequently reflect profound and deep-seated divisions within families, it is perhaps not entirely surprising that sometimes the parties themselves might prefer the estate to be consumed in legal costs, rather than be passed to those other members of the family with whom they disagree, or with whom they are in dispute. But there is an obligation, in my view, on the legal practitioners involved, nevertheless to ensure that the litigation is conducted efficiently, and the requirements of Rule 700A are to be applied, even if the parties are enthusiastic in fighting tooth and nail over every little point.”

Ultimately Judge McGill was unwilling to allow the executor their costs of defending the Family Provision Application on other than a reduced cost figure. The same applied to the Applicants because much of the material that had been filed was considered to be duplicitous and/or irrelevant to the issues in question.

Judge McGill further considered a decision of Her Honour Judge Rosengren from 2017, which also involved a Family Provision Application. In her reasons for judgement, Her Judge Rosengren rejected a submission made to her by the barrister appearing for the executor of the estate to the effect that the estate was entitled to be paid it’s costs from the estate on an indemnity basis as “a matter of right”. Her Honour stated “I do not accept this submission as it is premised on the assumption that the Court has no power to limit the parties, including the executor, in the expenditure of estate funds on applications of this type. This is clearly contrary to Rule 700A of the UCPR. It also ignores the fundamental principle that the executor’s costs to be recoverable from the estate ought to be properly and reasonably incurred.” Her Honour added “the costs ultimately remain in the discretion of the Court subject to the discretion being exercised judicially. This may include the capping or fixing of costs.”

The above decisions dispel any notion that Family Provision Applications are different to other types of litigation insofar as the Courts’ discretion with respect to the costs of the litigation is concerned. They are not in some special category whereby an Applicant for orders for Family Provision is entitled to their costs as of right, In addition, an executor of a deceased estate cannot expect, as of right, that all costs incurred by them in defending any Application and/or settling the same at mediation, or on trial, will be paid for by the estate as a matter or course.

In smaller estates, which as a rule of thumb comprise estates with a net value of less than $400,000.00, caution needs to be exercised with respect to the matter of costs incurred by the estate and by the Applicant for Family Provision Orders. Costs ultimately remain in the discretion of the Court subject to that discretion being exercised judiciously. The Court has power in these types of Applications to cap or fix the costs of each party involved in the litigation. It is the Court’s expectation that lawyers acting for the parties in these types of Applications attempt, at the earliest possible opportunity, to consult with each other and provide early advice to their clients as to the case at hand and the costs that ultimately will be incurred and have to be paid by them, without any guarantee of reimbursement from the deceased’s estate.

In summary, for smaller estates there is a critical need for an early and realistic assessment of any Family Provision Application, and the means by which the costs associated with either prosecuting or defending an Application, might be minimised as far as possible. If you are considering bringing or defending an Application for Family Provision Orders against a deceased person’s estate, or are merely seeking a second opinion as to your prospects of a current Application, our experienced solicitors would be pleased to assist you. Please contact our Litigation Team to arrange an appointment